Holy Week in Ruvo di Puglia

| Holy Week in Ruvo di Puglia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Official name | Settimana Santa di Ruvo di Puglia |

| Also called | Ruvestine Holy Week |

| Observed by | Ruvo di Puglia, Italy |

| Type | Christian |

| Celebrations | Processions |

| Begins | Friday of Passion (last Friday before Easter week) |

| Ends | Easter Monday |

| Frequency | Annual |

| First time | 16th or 17th century |

| Started by | Ancient local Confraternities |

The rites of Holy Week in Ruvo di Puglia constitute the main event held in the Apulian town. The folklore and sacred or profane traditions, typical of the Ruvestine tradition, are a great attraction for tourists from neighboring towns and the rest of Italy,[1] and have been included by IDEA among Italy's intangible heritage events.[2]

The rites begin on Passion Friday, preceding Palm Sunday, with the procession of the Desolate. Maundy Thursday is marked by the evocative night procession of the Eight Saints, while Good Friday is the turn of the mysteries. The procession of the Pieta on Holy Saturday concludes the penitential rites, while on Easter Sunday the procession of the Risen Jesus ends Holy Week.[3] All rites end on Easter Monday with the procession of the Virgin of the Annunciation in the village of Calendano.

History

[edit]

The confraternities in Ruvo

[edit]Evidence of the existence of early Ruvestine confraternities can be obtained from the polyptych, a Byzantine work initialed Z. T., depicting the Madonna and Child and brethren, in which appears the inscription "Hoc opus fieri fec(e)runt, confratres san(c)ti Cleti, anno salut(i)s 1537"[4] and preserved in the Purgatory church, in the left aisle, the one dedicated to St. Cletus.

The establishment of the Ruvestine confraternities was in the period of the Counter-Reformation, and at present there are only four sodalities still active. As reported by the polyptych, the earliest known confraternity is the Brotherhood of St. Cletus, whose praying brethren are depicted in the very painting dressed in white sackcloth and hooded. In the same period, Ruvo saw the establishment of the confraternity of the Most Holy Name of Jesus in the former Church of the Rosary, now St. Dominic's, by the Dominican fathers.

Other ancient and no longer active confraternities include the confraternity of the Conception and the confraternity dedicated to the Mount of Piety, which carried out charitable and welfare activities. Dated 1543 is the confraternity of the Blessed Sacrament founded in the co-cathedral of Ruvo di Puglia, whose confraternity members wore a purple habit and dedicated themselves to the care of the sick and the provision of dowries for two poor girls.[5] Among these early confraternities, special mention must be made of the sodality dedicated to St. Charles Borromeo, now no longer in existence, which played a very prominent role in Ruvestine society. This was followed, in chronological order, by the four active confraternities involved in Holy Week: confraternity of St. Roch (1576), archconfraternity of Carmine (1604), confraternity of Purgatory (1678) and confraternity Purification-Addolorata (1777).[6]

The four confraternities

[edit]The summary diagram summarizes the main features of the four still active confraternities, listed in order of age. The coats of arms of the four confraternities are superimposed on a field representing the dress of the brethren.

| Confraternity | Dress of the brethren | Dress of the sisters | Dress of the bearers | Penitential procession | Foundation year |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Confraternity Opera Pia san Rocco | White surplice, purple-red mozzetta and cincture, medallion depicting St. Roch (only during Holy Week do the brethren also wear white hood and black gloves). | Light blue scapular on which the initials MBC (from the Latin Mater Boni Consilii, Mother of Good Counsel) are embroidered. Only during Holy Week do the sisters also wear a black petticoat, a black veil and black gloves. | White surplice, purple-red bow, purple-red cincture, red scapular with image of The Transport of Christ to the Sepulcher by Antonio Ciseri, and black gloves. | Procession of the Deposition of Christ from the Cross, known as the Eight Saints, Maundy Thursday 2:30 p.m., St. Roch Church | 1576 (refounded in 1781)

|

| Archconfraternity of Carmel | White surplice, carmine-red mozzetta and cincture, medallion depicting Our Lady of Mount Carmel (only during Holy Week do the brethren also wear black gloves). | Carmine red scapular on which the initials MdC (Mother of Carmel) are embroidered. Only during Holy Week do the sisters also wear a black petticoat, a black veil and black gloves. | White surplice, carmine-red bow, carmine-red cincture, red scapular with holy card of the statue (the image varies for each simulacrum of the mysteries) and black gloves. An exception is made for Our Lady of Sorrows, whose bow, scapular and cincture are black. | Procession of the Dead Christ, Good Friday 3:30 pm, the simulacrum enters the cathedral (tradition maintained until 2016). At about 6:20 p.m., the Dead Christ joins the other eight mysteries, which had already left at 6 p.m. from the Church of Carmel, the moment when Our Lady of Sorrows gazes upon the face of her now-dead son. | 1604

|

| Confraternity of Purgatory under the title of “Mary Most Holy of the Suffrage” | White surplice, black shoulder strap and cincture, medallion depicting a skull with two crossed shinbones surmounted by a cross (only during Holy Week do the brethren also wear black gloves and white hood). | Black scapular with image depicting Our Lady of Suffrage on the front and the initials MSS (Mary Most Holy of Suffrage). Only during Holy Week do the sisters also wear a black petticoat, a black veil and black gloves. | White surplice, black ribbon bow, black scapular with holy card of the simulacrum and black gloves. | Procession of the Pieta, Holy Saturday 4:30 pm, Purgatory Church. | 1678

|

| Confraternity Purification Addolorata | White surplice, ivory mozzetta, black shoulder strap and light blue cincture, medallion depicting Our Lady of Sorrows (only during Holy Week do the brethren also wear black gloves and black hood). | Black scapular on which the initials MD (“Mater Dolorosa,” Mother of Sorrows) are embroidered on the front and back. Only during Holy Week do the sisters also wear a black petticoat, a black veil and black gloves. | White surplice, light blue bow, light blue cincture, medallion depicting Our Lady of Sorrows and black gloves.

The scapular changes on the occasion of the procession of the Risen Christ, whose imprinted image depicts precisely the simulacrum. |

Procession of the Desolate, Passion Friday 5:30 p.m., St. Dominic Church. Easter Sunday 9:30 a.m., Procession of the Risen Jesus. | 1777

|

Confraternity Opera Pia San Rocco

[edit]

With the dissolution of the Confraternity of St. Charles Borromeo in the late 16th century, the Confraternity Opera Pia San Rocco can be considered to all intents and purposes the oldest sodality still in activity in Ruvo. The origins of the cult of St. Roch are surely the result of Venetian influence,[7] which ruled the Adriatic Sea in the 1500s, but also of popular devotion: in 1502 the city of Ruvo was afflicted by a terrible pestilence, probably caused by the continuous clashes between the French and Spanish occupiers that resulted in the Challenge of Barletta.

St. Roch is said to have appeared in the guise of a wayfarer to both the first magistrate and the bishop of the then diocese of Ruvo, inviting them to pray.[8] A short time later the plague ended and as a sign of devotion in 1503 the townspeople erected a small church in his honor. According to legend, in the same church of St. Roch, the thirteen Frenchmen led by Guy la Motte, stationed in Ruvo, allegedly stayed overnight and attended holy mass before leaving for Barletta for the challenge.[9] The confraternity was founded on October 28, 1576,[7] as evidenced by the two wall inscriptions, one on the architrave of the entrance and one inside the church: it was Pope Gregory XIII who granted indulgences to the "confreres of Saint Roch of Ruvo." The social background of the brethren of St. Roch was undoubtedly humble, and in fact the forty brethren who signed the founding act of the congregation did so using a cross; they were illiterate peasants.[7] The sodality was described as poor in Bishop Gaspare Pasquali's 1593 report, so much so that the brethren lived on alms even to meet the expenses of restoring and decorating the church. The "relationes ad limina" (i.e., a report regarding the state of the diocese) of Bishops Saluzio, Memmoli, Caro, Alitto and Morgione infer the dissolution of the confraternity between the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, caused by a lack of funds that led to the silent and gradual demise of the sodality. On August 8, 1781, King Ferdinand IV signed the request for Royal Assent to the new confraternal statute, thus sanctioning the rebirth of the congregation. The new statute provided for assistance among the brethren themselves and the establishment of the Mount of St. Roch.

The small church of St. Roch began to be enriched with works of art commissioned by the brethren themselves, such as the 17th-century wooden statue of St. Roch, housed in the main niche above the altar; the oil painting, from the Neapolitan school, depicting Our Lady of Good Counsel, kept in a shrine displayed in the church; the silver statue of St. Roch by Giuseppe Sanmartino from 1793, kept in the cathedral, among other things displayed during the Covid-19 emergency in 2020, to invoke the saint's intercession and appease the pandemic. On March 16, 1919, the confraternity of St. Roch decided to provide itself with a simulacrum to be paraded during Holy Week:[10] the task was assigned to the Lecce papier-mâché master Raffaele Caretta, who was inspired by Antonio Ciseri's 1883 painting The Transport of Christ to the Sepulcher. The simulacrum fully and dramatically depicts the same characters as in Ciseri's work; leading the group and supporting the shroud in which Jesus' lifeless body is wrapped are Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus in front and St. John supporting the sheet behind Christ; completing the group are Mary of Clopas, who holds an almost fainting Mary, Salome and a penitent Mary of Magdala.[11] The statuary group made its debut on April 17, 1920, and first crossed the threshold of the church of San Rocco in the late afternoon; the same scene is still repeated today with Pancaldi's Eternal Sorrow funeral march that begins the procession, moved since 1921 to the usual night time of 2:30 a.m.[12] In 2020, the processional rite was not held, due to the Covid-19 emergency, despite the 100th anniversary of the simulacrum.

Archconfraternity of Carmine

[edit]

The archconfraternity of Carmine contrasts with the modesty of the confraternity of San Rocco. Founded on May 15, 1604 on behalf of clergymen and noblemen,[13] after Bishop Gaspare Pasquali had approved the confraternity's statute, it soon became the most wealthy and influential in the Ruvo scene: one-third of the original 141 confraternity members were clergymen.[13] The fledgling confraternity found its headquarters in the church of Saint Vitus, entrusted on the condition that the brotherhood would engage in its restoration: the same church, once the renovation was completed, was named after Our Lady of Mount Carmel, titular of the archconfraternity of the same name. The original statutes stipulated that the rector delegated to two brethren the task of visiting the prisoners, assisting the sick and collecting alms every Thursday.[13]

During harvest periods, a couple of brethren would roam the Ruvestine countryside in search of provisions to store for the winter and which would flow into the Monte di Pietà. In 1690 the notary Carlo Barese designated the archconfraternity of Carmine as the universal heir of his wealth upon the death of his two sons, priests Alessandro and Nicolò, replenishing the coffers of the sodality.[14] In the seventeenth century, the brethren decided to equip themselves with wooden simulacra representing the sacred mysteries and to be paraded on Good Friday. The newly restored church took the name Carmelite Church for two reasons: there is a fresco, representing Our Lady of Mount Carmel, on the vault of the church and also the Carmelite bishop Sebastiano D'Alessandro was buried there. Despite this, signs of the cult of Saint Vitus are still visible, as evidenced by the painting depicting Saint Vitus between Saints Modestus and Crescentia.[15]

A burial ground was reserved in the church for the brethren and there were also tombs of Ruvestine nobles, including Luca Cuvilli and Antonio Miraglia. Records of the procession of the mysteries date back to the 17th century, but the history of the now traditional Good Friday procession suffered a moment of crisis in the mid-20th century: from the original number of 13 statues and sacred vestments, the procession saw the number of simulacra decrease first to 10 and then to 8, with the removal of the statues of St. Peter, St. John and Veronica, then abruptly from 8 to 4 due to the lack of bearers. It is only since the 1980s that the Archconfraternity of Mount Carmel has been engaged in reintegrating 4 more statues into the procession, bringing the total number to 8 (Jesus in the Garden, Jesus at the Pillar, Ecce Homo, Jesus at Calvary, Jesus Crucified, Dead Jesus, Mary of Sorrows, and the Holy Wood).[16] In 2018, the simulacrum of Veronica was also reintroduced into the processional rite, with the intention of bringing the number of statues in the procession back to 11. In 2020, the processional rite was not held, due to the Covid-19 emergency.

Confraternity of Purgatory under the title of “Mary Most Holy of the Suffrage”

[edit]

The Confraternity of Purgatory can be considered to all intents and purposes the main heir of the first known Ruvestine confraternity, the Confraternity of San Cleto.[5] St. Cletus, according to popular legend, is said to have been appointed the first bishop of Ruvo by St. Peter himself, who stopped at the Ruvestine “station” on the Appian Way; later, in 80 A.D., Cletus or Anacletus was elected third pope,[17][18] and after his death, he was immediately venerated by the Ruvestine people, who elevated him to the status of town patron. His ancient cult is also evidenced by the limestone statue depicting Saint Cletus in the Roman-era cistern in the basement of the Purgatory Church.[18]

As the centuries passed and the city developed, the church of Our Lady of Suffrage was built above the cave of St. Cletus, which constituted a true center of worship. The building, dating from the 1500s, saw the rise of the confraternity of San Cleto, as evidenced by the aforementioned polyptych dated 1537. In the early seventeenth century the Ruvestine noblewoman Elisabetta Zazzarino expressed the desire to build a small church dedicated to the Souls in Purgatory.[19] Thus a second nave centered on the worship of the Purgatory Souls was added to the Suffrage Church. The new church, complete with two naves, was first named after St. Michael the Archangel and only a few years later was renamed, as it is called today, Purgatory Church. On August 27, 1678, the bishop of Ruvo, Domenico Galesio, founded the confraternity of Mary Most Holy of the Suffrage of Purgatory by aggregating it with the archconfraternity of the Suffrage of Rome.[19]

The new confraternity was also immediately the object of attention from the noble families of Ruvo, whose bequests contributed to the establishment of as many as three charitable Mounts: the Mount Purgatory, Mount Leone and Mount San Cleto. The Mount of the Dead was immediately established thanks to the alms that the faithful contributed in order to receive as many memorial masses as the sums of money they contributed. The confraternity provided for the care of the poor, the sick and widows and the establishment of dowries for poor maidens. The sodality received Royal Assent from Ferdinand IV in 1766.[19] During this period the church was provided with works of art, such as the canvas depicting Our Lady of Suffrage among the Purgatory Souls by Carlo Plantamura, vestments as well as silverware and sacred jewelry. In 1898, owing to the alms collected, the brethren and sisters purchased the simulacrum of the Pieta made by Lecce papier-mâché master Giuseppe Manzo; it is from that year that at 4:30 p.m. sharp on Holy Saturday, the statue of the Pieta, carried on the shoulders of 38 bearers, wanders through Ruvo concluding the rites of Ruvestine Holy Week. In 2020, the processional rite was not held, due to the Covid-19 emergency.

Confraternity Purification-Addolorata

[edit]

The Dominican Order settled in Ruvo in the second half of the 16th century under the protection of some local noble families. The Dominican Fathers left their trace in Ruvo through the building of the convent, around the 1720s, behind the Church of Our Lady of the Rosary.[20] With the arrival of the Jesuits in Ruvo, mainly thanks to the industriousness of Domenico Bruno, a Jesuit from the college of Bari, the Purification-Sant'Ignazio confraternity was founded in 1719 in the church of St. Charles. Bruno's intent was to religiously form the peasants and poor population of Ruvo.

A few years later the confraternity moved its headquarters to the church of Our Lady of St. Luke, now the shrine of the Holy Doctors, where meetings and the exercise of piety took place.[21] It was probably during this period that the painting, now preserved in the church of St. Dominic, representing the Presentation of Jesus to the Temple and Purification of Mary, a theme so dear to Domenico Bruno, was commissioned. In fact, the canvas is venerated both by the confraternity, as it symbolizes the Purification of Mary to whom the sodality is dedicated, and by the population on the occasion of Candlemas. The Jesuit father himself implanted in the confraternity the cult of Our Lady of Sorrows to be observed on Passion Friday, at that time the day of the liturgical feast.

Bruno considered it essential to use sacred figures to educate the population, especially the most ignorant and illiterate:[20] an 1805 inventory compiled by the confraternity members reveals the presence of no less than two statues of Our Lady of Sorrows, a statue of St. Vincent Ferrer, a Dominican preacher, a wooden statue of St. Dominic, and two other important canvases, one concerning Our Lady of Graces by Fabrizio Santafede, the other Our Lady of the Rosary by Alonso de Corduba.[22] Following the suppression of the Society of Jesus, the confraternity disbanded in 1768 only to be refounded almost ten years later by some former brethren. In 1777 it obtained Royal Assent under the name of the Confraternity of the Purification, receiving, however, quite a bit of criticism from the townspeople but especially from the Archconfraternity of the Carmine, both because of arguments concerning precedence in processions and because the confraternity had been able to get Ferdinand IV to approve the reworked statutes of the previous Jesuit-style brotherhood, a religious order suppressed by the same king a few years earlier.[21] In the early nineteenth century the congregation moved to the new church of St. Dominic, built on the church of Our Lady of the Rosary, governed by the Scolopian fathers. In 1794, the confraternity commissioned a Neapolitan artist to make a statue depicting Our Lady of Sorrows: so central was the cult of the Virgin that on March 28, 1833, Pope Gregory XVI added the title “Our Lady of Sorrows” to the congregation's name.[23] In 1866 the order of the Scolopi was suppressed and the Ruvo city council, only a year later, ceded the church of St. Dominic to the now established confraternity of the Purification-Addolorata.[23] Thus arrived in Ruvo the new simulacrum, also known as Desolata, and in 1893, on Passion Friday, it crossed the threshold of St. Dominic's church for the first time. In 2020, the processional rite was not held, due to the Covid-19 emergency.

The adoration of the cross by the four confraternities.

[edit]Throughout Lent, the rite of the Adoration of the Cross is officiated, a very ancient rite maintained by the confraternities that is held in preparation for Holy Week. The rite is celebrated on Tuesdays, Wednesdays and Fridays in the churches that host the organizing confraternities.

The band

[edit]

The band with its funeral marches is the undisputed protagonist of Ruvestine Holy Week. The task of the band, in addition to accompanying the procession, generating fascination in the spectator, is to pace the typical slow, rocking steps of the numerous bearers.[24][25] As in the rites of neighboring towns, similarly to Ruvo, characterized in the past two centuries by the assiduous activity of the various musical schools (for instance, Molfetta or Bitonto), a good part of the funeral marches performed was composed by local composers such as the brothers Antonio and Alessandro Amenduni and the maestro Basilio Giandonato; nowadays this practice is continued by the current band directors, Rocco Di Rella and Gennaro Sibilano, both maestros from Ruvo.

The band consists of the classical instruments such as clarinets, oboe, flutes, saxes, horns, saxhorns, drums, bass drums, cymbals, trumpets, trombones and tubas,[26] but also of two particular instruments, moreover common to many Apulian rituals, such as "u tammùrre" (drum in Ruvestine dialect) and the "truozzue" (the typical troccola): these two instruments have precise functions: the drum, an hour before the exit of the simulacra, makes a tour around the city while beating to call the townspeople in view of the exit of the procession, which, among other things, will then follow, accompanied by the bass drum; the troccola, on the other hand, is carried in the procession, because the incessant beating is a reminder of the hammer that nailed Jesus to the cross.[27] The Ruvo band was formed in the early 1900s, after the various "da giro" bands formed in the second half of the 1800s.

The best period of the band was experienced under the direction first of Antonio Amenduni and then of his brother Alessandro,[28] both pupils of maestro Francesco Porto, author of the funeral march Povero Ettore, who brought to high levels the city band ensemble that debuted as a “boys' band” on June 7, 1925.[29] Another maestro, of no less importance, was Basilio Giandonato. The sounds that serve as the soundtrack to Ruvestine Holy Week also feature pieces by non-local composers, such as Una lagrima sulla tomba di mia madre by Amedeo Vella (performed at 2 a.m. on Holy Thursday in Piazza dell'Orologio), the famous Piano Sonata No. 2 by Frédéric Chopin,[30] Roberto Bartolucci's Milite ignoto, Raffaele Caravaglios' Perduta, Errico Petrella's Jone, Angelo Lamanna's Holy Saturday and Pieta (performed at the Holy Saturday procession) and Luigi Cirenei's Requiescat in pace.

There are currently two bands that play funeral marches during Ruvestine Holy Week, the Concerto Bandistico "Basilio Giandonato" directed by maestro Rocco di Rella, and the Concerto Bandistico "Nicola Cassano" directed by maestro Gennaro Sibilano. Below is the list of funeral marches that accompany the Holy Week processions in Ruvo:[25][30]

- The weeping of the orphan by Antonio Amenduni

- How many tears by Antonio Amenduni

- Eternal Rest by Antonio Amenduni

- Sadness by Antonio Amenduni

- Heartbreak by Antonio Amenduni

- Resignation by Antonio Amenduni

- Planctus Mariae by Antonio Amenduni

- Poor Ettore by Francesco Porto

- Eternal Rest by Alessandro Amenduni

- Sad remembrance (or to my father) by Alessandro Amenduni

- Resignation by Alessandro Amenduni

- Great Loss (or to my mother) by Alessandro Amenduni

- Day of Sorrow by Alessandro Amenduni

- Vivid condolences by Alessandro Amenduni

- Grieving by Alessandro Amenduni

- Inconsolable sorrow by Alessandro Amenduni

- Sad remembrance by Alessandro Amenduni

- Last farewell by Alessandro Amenduni

- Bitter Tears by Alessandro Amenduni

- The Desolate by Basilio Giandonato

- In memoriam by Basilio Giandonato

- Sadness by Basilio Giandonato

- The Deposition by Basilio Giandonato

- Requiem by Basilio Giandonato

- The Pieta by Basilio Giandonato

- Piano Sonata No. 2 by Frédéric Chopin

- Jone by Errico Petrella

- A tear on my mother's grave by Amedeo Vella

- Lost by Raffaele Caravaglios

- Eternal Sorrow by Evaristo Pancaldi

- Requiescat in pace by Luigi Cirenei

- Unknown Soldier by Roberto Bartolucci

- Maria Santissima del Suffragio by Rocco Di Rella

- Ecce Homo by Rocco Di Rella

- Little Angel by Gennaro Sibilano

- Jesus in the Garden by Gennaro Sibilano

- Elegy by Gennaro Sibilano

- Lost by Giuseppe Pellegrini

- Calvary by Vincenzo Jurilli

Statues

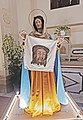

[edit]Confraternity Purification-Addolorata Maria Santissima Desolata

[edit]Maria Santissima Desolata

[edit]

It is dated Feb. 19, 1893, the decision of the Purification-Addolorata confraternity to insert itself in the rites of Holy Week with a penitential procession on Passion Friday, the day on which people commemorate the Seven Sorrows of Mary whose cult was carried on, in Ruvo, by the Jesuit Domenico Bruno.[31] The first simulacrum of Our Lady of Sorrows, dubbed Desolate (a typical name given to statues depicting Our Lady of Sorrows near the bare cross), that came into the hands of the confraternity was of Neapolitan design, as recalled by an engraving on the trestle. The statue first crossed the threshold of St. Dominic's church on Passion Friday, April 8, 1893. In 1907, however, a meeting of the confraternity attests that the state of the statue, only thirteen years after its creation, was disastrous with scratches and cuts on its face and cracks on its hands.[31] The decision to be taken as a result of this meeting would be the commissioning of a new simulacrum.

The old statue consisted of a wooden cross with brass edging, while the figure of Our Lady of Sorrows was composed of a half-length mannequin with jointed arms both at the elbows and at the attachment to the shoulders. Molfettese artist Corrado Binetti was commissioned to remake the simulacrum, as attested by the inscription "Corrado Binetti - 1907 fece - Molfetta" present on the Madonna's right shoulder. Binetti remade the half-bust but used the same cage-like support, made in Naples, on which the statue was fixed. The cross was also redone to fit the new simulacrum: the wooden and brass cross was replaced by an iron skeleton covered with cork.[31] The statue is carried on the shoulders through the streets of the city by forty bearers: the simulacrum itself, on the occasion of the procession, is placed on a wooden crate bearing the symbols of the Passion, of mid-twentieth-century workmanship.[31] As tradition would have it, on this day, gusts of wind blow, so much so that the people of Ruvo have given the Desolata the appellation “Maduònne du Vinde,” or Madonna of the Wind. Tradition has it that, in the last stretch of the processional route, the brethren arrange themselves at the beginning of the procession, while the sisters take their places to follow them, hugging the Virgin in a symbolic embrace.[32]

Risen Jesus

[edit]

Since 1922 the Purification-Addolorata confraternity, in addition to initiating the rites of Ruvestine Holy Week, has concluded them with the procession of the Risen Jesus on Easter Sunday. Little is known about the original simulacrum that paraded through the streets of Ruvo starting in 1922. However, the current papier-mâché statue depicting the Risen Christ, by Salvatore Bruno of Bari, dates back to 1952.[33]

Confraternity Opera Pia San Rocco

[edit]Deposition of Christ from the Cross, known as the “Eight Saints”

[edit]

Although the confraternity of San Rocco is the oldest still in operation, it was the last to acquire a simulacrum to be included in the Holy Week penitential processions. The sums paid for the purchase of the statuary group are unknown, but instead the confraternity's desire to possess a group capable of fully impressing the Ruvestine people once carried in procession is well known. In 1919 the sodality commissioned the creation of a simulacrum to be carried in procession during Holy Week depicting the transportation of Christ to the tomb and, as mentioned above, capable of impressing the people.

Another objective that the creation of the work in question had in mind was, above all, the financial return for the confraternity: a work of this magnitude would certainly increase the offerings of the faithful.[10] The statue was made by Raffaele Caretta from Lecce, in devotion to the noblewoman Rosina Ruta de Tommaso:[34] the master papier-mâché maker was inspired by Antonio Ciseri's painting depicting the Transporting of Christ to the Sepulcher, drawing from it a papier-mâché statuary group that renders well the idea of the drama and pain of the moment,[35] however, Caretta diverged from the Italo-Swiss painter by shaping a still young and beardless Saint John and placing a little angel above the papier-mâché group.[36] Completed in 1920, as evidenced by the inscription at the foot of the Magdalene, “Cav. Caretta Raff. Lecce 1920," the simulacrum arrived in Ruvo in its final version: however, the confraternity, in order to make the statuary group more spectacular, added characters and radically altered the statue by using papier-mâché mannequins dressed in robes and wearing wigs.[37]

Soon, however, the current simulacrum was restored: the statuary group has a horizontal development from left to right, and to highlight the group's descent from Mount Golgotha, Caretta modeled the base so that it would be higher at the end of the group. On the evening of Maundy Thursday, April 17, 1920, the imposing simulacrum appeared outside the small door of the small church of St. Roch, although the work, for the first twelve years, had been allocated in the large niche of the newly consecrated Church of the Redeemer (where the simulacrum of Our Lady of the Rosary is located today),[38] until the existing compartment was created in the mother church of the confraternity.

The impact on the population was immediate and extraordinary but above all consoling:[39] the mothers and families who had lost their sons in the war identified well with the grief of the distraught and pale Mary of Sorrows, and the transport to the tomb of Christ stood as a substitute for the many missed funerals for the young men, husbands and fathers who had fallen at the front.[39] The atmosphere charged with pathos and suggestiveness that accompanies the procession of the Eight Saints has made it the symbolic simulacrum of Ruvestine Holy Week.[39][40] The statuary group is called the Eight Saints, since there are eight figures that compose it:[12] Nicodemus and Joseph of Arimathea carrying Jesus, wrapped in the shroud, holding him by the feet; a very young St. John holding the sheet behind the lifeless Christ; Mary with her eyes turned to heaven and the crown of thorns in her hand, pale and wracked with pain, is supported by Mary of Clopas flanked by a penitent Mary of Magdala and a weeping Salome.[12]

Between October 2001 and March 2002, the sculptural group underwent major restoration work that restored the simulacrum to its original colors and removed additional and superfluous layers of papier-mâché.[41] In October 2011, the old semicircular stained-glass window on the facade of the church of St. Roch was replaced with a polychrome stained-glass window depicting the statuary group of the Eight Saints.[42] Between April 2013 and February 2014, the simulacrum was restored again, correcting the chrome plating and highlighting some details.[43] In 2020, the statuary group celebrated the 1st centenary since its creation.

The Eight Saints

[edit]-

Jesus dead

-

Mary

Archconfraternity of Mount Carmel

[edit]Mysteries

[edit]

The Good Friday procession of the mysteries is the oldest within the penitential processions of Holy Week.[44] The simulacra, all wooden, considering only the eight that parade now, are kept in different niches in the Carmine Church. Three of the six Christs, namely Jesus in the Garden, Jesus at Calvary and Dead Jesus, are the work of Altamura sculptor Filippo Altieri, who died at only 39 years old. The most revered statue is undoubtedly that of Jesus at Calvary, representing precisely the ascent of the cross-bearing Christ to Calvary:[45] the statue, made from a cherry tree trunk in 1674, is an object of worship: many are the ex-votos and offerings, not only in money, but also in jewelry and gold and silver objects. In fact, the statue depicts a scourged and bloody Christ suffering while supporting the weight of the cross.

Because of its expressive charge and the devotion of the people, in August 1980, but also at some earlier times, the simulacrum was carried on the shoulders to the countryside during a time of great drought requesting Christ's intercession.[46] Even today it is still possible to see, during the procession, the large number of the faithful parading behind the simulacrum as a sign of devotion: some of the faithful even march through the city barefoot, and there is no shortage of heartbreaking cries from the faithful as Christ passes.[45] Over the years, the simulacrum has undergone various restorations, most frequently those of the 20th century: the effigy underwent a first restoration in 1884, when the old base was replaced; a second restoration was in the 1970s that, in addition to the revision of the wooden simulacrum, altered the color of Christ's robe from red to a lobster color; in 1993, however, the restoration brought the robe to a burgundy color while the face went from ochre to pale, almost white, with unlikely rivulets of blood. In 2011 the statue was restored for the fourth time by Leonardo Marrone of San Ferdinando di Puglia, bringing the tunic and face back to its original color.[47]

Another particularly venerated statue is the dead Christ, in polychrome wood, lying in a shroud. The other simulacra that form part of the group represent Jesus in the Garden, Jesus at the Pillar, Ecce Homo, Jesus Crucified, Our Lady of Sorrows, representing Our Lady in Mourning with her gaze turned toward heaven and followed by a small number of worshippers, concludes the Holy Wood,[48] a wooden temple of oriental type, in which on a pedestal is placed a silver cross containing a fragment of the True Cross.[45] Today's small temple dates back to the early 2000s and replaces an old structure that in turn replaced one that was completely destroyed by fire on Good Friday in 1956.[44][49] The splinter of the true cross was brought from Rome to Ruvo by Carlo Marinelli and delivered to the primicerius Don Carlo Quatela on March 8, 1724.[50]

The procession of the mysteries, although being the oldest, has experienced moments of crisis: until the 1950s, in fact, the procession was composed of as many as 11 simulacra; to the eight currently parading were added the statues of St. Peter, Veronica and a very young St. John (all in papier-mâché and of modest workmanship)[51] that preceded the holy wood with the task of concluding the procession. After a few years, however, the composition of the procession of mysteries changed from 11 to 4: Jesus at Calvary, Dead Jesus, Our Lady of Sorrows and the holy wood. The drastic shift was due to the lack of bearers, so the four most representative statues were chosen. This formation remained intact until the arrival of the new millennium, where at the behest of the archconfraternity the current number of eight simulacra was established.[16]

However, the problem of bearers has not been completely solved; in fact, some bearers from other Ruvestine confraternities lend themselves as bearers to the archconfraternity of Carmine. Recently in the archives of the Purification-Addolorata confraternity a significant document was found that represented a pact, among the four Ruvestine sodalities, regarding the procession of the mysteries: the four confraternities would have to actively participate in the Good Friday procession, on the same model as the procession held in other Apulian cities such as Molfetta, Giovinazzo or Terlizzi. Each congregation, in fact, would have been obliged to carry two simulacra on their shoulders, excluding the dead Christ, Our Lady of Sorrows and the holy wood; in addition, the four confraternities would have had to share the expenses and provide bearers and officiants. Despite the signature of the then Bishop of Ruvo, Monsignor Andrea Taccone, in 1930, there is insufficient evidence to verify whether or not the stipulated agreement was put into practice, as is still the case today. Probably with the advent of World War II and the departure of men for the front, the pact fell apart, leaving the care of the Good Friday procession exclusively entrusted to the archconfraternity of Carmine.[52] The procession of the mysteries in 2012 underwent a change as the crucifix statue belonging to the archconfraternity was replaced with the wooden sculpture of Christ Crucified venerated in the cathedral, due to the poor condition of the simulacrum. In 2013, the congregation decided to permanently replace the papier-mâché Christ Crucified with a perfect copy made of pine wood of the aforementioned simulacrum in the cathedral, handmade by Stefan Perathoner of Urtijëi. As of 2018, the procession of the eight mysteries was enriched with the introduction of the simulacrum of Veronica, following the Archconfraternity's desire to gradually employ the simulacra of the Mysteries whose transportation had fallen into disuse.[53] The statue of Veronica underwent restoration work, as did the statue of Jesus in the Garden, which underwent extensive restoration in 2022.[54]

The nine statues of the mysteries

[edit]-

Jesus in the Garden of Olives

-

Jesus at the pillar

-

Ecce Homo

-

Jesus at Calvary

-

Veronica

-

Jesus crucified

-

Dead Christ

-

Mary of Sorrows

-

The Holy Wood

Confraternity of Purgatory “Mary Most Holy of the Suffrage”

[edit]The Pieta

[edit]

The image of the Pieta, the symbolic procession of the Purgatory Confraternity, was commissioned following the confraternal resolution of April 23, 1897[55] and made between 1898 and 1901.[11] The simulacrum, the work of Lecce master papier-mâché maker Giuseppe Manzo, is clearly inspired by the much more famous Vatican Pietà sculpted by Michelangelo Buonarroti. The making of the statuary group was covered financially by the oblations of members and the faithful.[55] The decision to entrust Manzo with the task of shaping the simulacrum was not accidental: Manzo is also famous for having created three of the mysteries of Taranto, namely Jesus at the Pillar, Ecce Homo, and the Waterfall; furthermore, Manzo had already collaborated with the Purgatory confraternity by making statues depicting St. Expedite, Our Lady of Martyrs, St. Rita, and St. Anthony.[11] Between 1898 and 1901 the simulacrum of the Pieta paraded with the structure designed by Manzo but with the papier-mâché parts (the face and hands) taken from a simulacrum of Our Lady of Sorrows present in the Purgatory church.[55] The head and hands of Our Lady of Sorrows were completed in 1901 while the Christ lying on his mother's lap was not completed until 1928 and until then replaced with a temporary simulacrum.[55] The restoration operation led in 2004 by Leonardo Marrone of San Ferdinando di Puglia led to the discovery of a certificate of merit, placed under the Madonna's neck, to the sculptor Manzo for the gold medal at the 1898 General Exhibition of Sacred Art in Turin.[55]

The statue, displayed in the first niche of the Purgatory Church, depicts Our Lady in Mourning seated on a boulder at the foot of the cross, on which hangs a white sheet depicting the shroud, and with her son lying on her lap and looking up to heaven.[56] Above all, the beauty of the statue of Mary, “white in face but beautiful in her pain,” emerges.[57] The procession and the simulacrum of the Pieta are particularly dear to the Ruvestine women and to the sisters: the simulacrum was a fundamental figure during the war years, because women - identifying with Mary's grief over the loss of their child - assimilated her pain and became attached to the simulacrum that seemed capable of understanding their sorrow as mothers.[58] This venerated statue, too, on par with the Jesus at Calvary of the Archconfraternity of Mount Carmel, was the recipient of numerous donations from the population, which until recently were hung at the base of the simulacrum, until the bishop of the diocese banned its use to urge penitential processions to limit their pomp.[56] The Pieta statue was repeatedly invoked by the population over the decades to cope with the many famines that had occurred.

From 1898 to 1957, the procession took place on Holy Saturday morning, starting from the Purgatory Church at the crack of dawn while from the following year until the present day the procession began to parade in the middle of the afternoon.[55]

The rites of Holy Week

[edit]Lent

[edit]Ruvestine Shrove Tuesday leaves its traces in the absolute silence of the night, once the popular celebration of the funeral of "Mbà Rocchetidde" (Ruvestine's popular mask, which impersonates the carnival) is over.[59] On the night approaching Ash Wednesday, “Quarantanas” are hoisted at various points in the city: the Quarantana is a woman's puppet representing the wife of the deceased Carnival and thus dressed in mourning. The puppet carries in her hands a spindle and an orange on which seven chicken feathers are stuck, symbolizing the weeks of Lent, which one at a time are removed Sunday after Sunday.[60] Ash Wednesday marks the beginning of Lent, a time of reflection and spiritual preparation toward Holy Week. During the forty days leading up to Easter, the four confraternities gather for acts of spiritual aggregation. In turn, the act of the Adoration of the Cross is held in each mother church of the confraternities, which consists of the kissing of a crucifix held by a confrere belonging to the various sodalities in the church who are arranged among the members in order of age. The rites of Lent come to an end about a week before Palm Sunday, when the Purification-Addolorata confraternity starts the novena to Mary Most Holy Desolate.[61]

Passion Friday

[edit]

Procession of the Desolate

[edit]In the days leading up to Passion Friday, the church of St. Dominic, the headquarters of the Purification-Addolorata confraternity, began to echo the funeral marches with the traditional Passion Wednesday concert. In the middle of the Friday afternoon, "u tammurr" strikes the first beats and calls the population to gather in Bovio Square.[62] Meanwhile, in Garibaldi Square, at 5 p.m., the band performs the first funeral march Triste ricordo (To my Father), by Alessandro Amenduni. It is a tradition for the brethren to start the day with a pilgrimage to the shrine of the Most Holy Savior in Andria.[62] The frequent spring wind, which often characterizes Passion Friday, has led the Ruvestine population to call the Desolata the “Maduònne du vìnde” (Our Lady of the Wind).[62]

At 5:30 p.m. the door of St. Dominic's Church opens and the simulacrum of the Desolate appears carried on the shoulders of the forty bearers who are escorted by the brethren wearing black hoods amid clouds of incense.[63][64] Immediately the band strikes up with Pancaldi's Eterno Dolore funeral march. The simulacrum, after the continuous rocking on the churchyard waiting for the end of the first funeral march, is placed on the “forcelli” for a few minutes and at the same time the sisters and confreres arrange themselves in the two wings in a row preceding the statue. The procession departs at a slow, rocking pace cadenced by the funeral marches, and between the statue and the band, which closes the procession, the faithful and civil authorities enter.[65]

To the sound of the bass drum that opens the procession, white cloths that symbolize the shroud emerge from the balconies and represent a feature still present only in Ruvestine Holy Week rites.[66] The procession passes through all the main streets of the historic center, and the waning darkness makes the procession illuminated by the various lamps even more impressive. After stopping in front of the hospital, the procession moves on to the retreat scheduled for 10:30 p.m. in Bovio Square, the site of St. Dominic's Church.[67] Corso Carafa, which precedes the square, is completely darkened, creating a special atmosphere as the simulacrum passes through the square between two wings of the crowd lit only by the candles of the brethren and sisters, who in the meantime swap their positions so as to arrange the men to open the procession and the women to protect the statue.[67] In this section the hymn "Prayer to Mary Most Holy Desolate" is performed, sung by the brethren and sisters, which is followed by the funeral march A Tear at My Mother's Tomb by A. Vella.

After the spiritual father's final blessing, the band marks the slow entrance of the statue into the church with the last funeral march, namely Jone by Errico Petrella.

Palm Sunday

[edit]Palm Sunday is presented as the last day of celebration before the “Great Week.” In the morning in all the churches of the city, primarily in the cathedral, the various blessings of palms take place, replaced by large and leafy olive branches.[68] While the morning is marked by church services and hearty lunches, in the late afternoon it is the confraternity of St. Roch that gathers in the small church of the same name, where the Eight Saints are already on display, to begin the triduum of preparation for the Holy Thursday gala procession. In the evening, the bishop, having arrived in Ruvo from Molfetta, leads the diocesan Way of the Cross that reaches the main points of the city.[69]

Holy Wednesday

[edit]For the past few years the tradition of the sacred representation present until the early 2000s has been revived. The sacred representation, curated by the Archconfraternity of Carmel, represents the prelude to the Paschal Triduum, a day of "pathos" and suggestiveness for the entire Ruvestine citizenry.[70][71] Meanwhile, in Matteotti Square, as evening falls, the floral arrangement of the statue (begun on Tuesday evening) is already complete in the small church of St. Roch, and the last instructions on the organization of the procession are laid out.

Outside the small church, since 2009 it has been customary to hold a concert of funeral marches by the " Friends of St. Roch" band in anticipation of the night procession.[72]

Maundy Thursday

[edit]Procession of the Eight Saints

[edit]

In the early hours of Maundy Thursday, "u tammurre" begins its route through the dark streets of Ruvo. Little by little, the Ruvestines leave their homes and make their way to Menotti Garibaldi Square to watch the funeral march, performed at 2:00, A tear on my mother's grave by Amedeo Vella. Meanwhile, Matteotti Square is swarming with people, not only residents but also worshippers who have come from neighboring towns along with tourists, onlookers[72] and the many emigrants returning to their homeland for Easter.[73] By 2:30 the band has already reached the square.

The sisters arrange to open the procession, while the brethren remain near the church. The blasts of cymbals and trombones open the funeral march Eterno dolore (Eternal Sorrow) by maestro Evaristo Pancaldi when the forty bearers are already bringing the imposing simulacrum out of the small door of the church of San Rocco, holding it with their hands down by the bars.[73]

The population in the square maintains silence, fascinated by the special atmosphere that is the result of the intertwining of the skill of the bearers, who with effort and care extract the sculptural group, and the funeral march that cadences its rhythm.[73] After a few minutes the statue is already on the shoulders of the bearers, who with the classic rocking motion carry it to the parvise. Once the procession has been arranged, the statue makes its way around the square and then winds its way through the dense and narrow streets of Ruvo's historic center, making the atmosphere that accompanies the nighttime procession of the Eight Saints even more evocative, with the various alleys illuminated only by the faint flames of candles carried by brethren and sisters lashed by the spring wind.[74] After an hour or so from the exit of the procession, the procession reaches the esplanade in front of the co-cathedral and makes its way to the Church of the Purgatory, just a hundred meters ahead, purposely left open with the statue of the Pieta in the foreground. The simulacrum, having arrived in front of the entrance to the church, is spun around to simulate the meeting of the two Marys suffering from the same pain. The procession then resumes its journey heading toward the hospital. At dawn, the brethren and bearers, visibly tired,[74] after almost reaching the outskirts of the city, aim to walk through the main streets of Ruvo, the last long stretches in view of the retreat. As morning arrives, onlookers and spectators throng the streets. Almost at 9:00 a.m., the simulacrum prepares to make the last climb, the one up Corso Gramsci that leads directly to Piazza Matteotti, home of the church of San Rocco.

The population is gathered in the square as the procession approaches the small church with the Jone march by maestro Errico Petrella, the true soundtrack of the entire procession. The mournful and pathetic notes lend themselves well to the return of the statue to the church, which is brought back inside holding the face of the statuary group facing the square, after a prayer by the spiritual father. Spontaneous applause arises from the audience, once again addressed to the skill of the bearers capable of getting the simulacrum out and back in through a seemingly narrow and small door.[74]

Mass in coena Domini

[edit]In all parishes in Ruvo, especially in the co-cathedral, the so-called Mass in coena Domini is held. The priest assisted by the mayor reenacts the episode of the washing of the feet performed by Jesus, who girded his waist with a towel washed the feet of the twelve apostles, on this occasion represented by 12 needy people of the city.[75] At the end of the solemn ceremony, the sacramental bread is closed in the altar of repose, erroneously called “sepulcher” by tradition.[76]

The Sepulchres

[edit]The sepulchre, called in dialect "sebbùolch," indicates the place (repository) where the consecrated host was placed, but also the characteristic scenery set up around the tabernacle, now very distant from those of the past,[77] as well as the organization and ritual of visits to the sepulchres as the artist Domenico Cantatore, a native of Ruvo di Puglia, recalls in his story Aria di Aprile:

At vespers that day, my mother dressed me in a velvet gown with a starched collar, put on a black cap as a sign of mourning, and took me with her to visit the graves. [...] On entering the first church, my mother pulled her veil over her face and placed her hands crossed on her chest. The interior of the church was bathed in darkness, and the few candles that were lit seemed far away. The tomb, raised above the main altar to the arch of the nave, with a large cross and long cypress trees, looked grim and solemn. Below, illuminated by a pale light, was the rock of the tomb, surrounded by a meadow of tender sprouts of leguminous plants. Through a glass one could see Jesus lying there, bleached by death, with the blood of his wounds clotted: he looked like a real man. Visitors knelt before him, bowing their heads and beating their fists on their chests. Women crawled on the polished floor in small steps, praying softly, absent from each other like opaque shadows. [...]

From one church to another we met the Marys, carried by men in white robes, their faces covered by a hood. The Madonnas, illuminated by a pyramid of candles at the base, went in search of their Son, stopping for a few minutes at each church's wide open door. The seven statues from the seven parishes, followed by the barefoot faithful, continued to walk through the night and until dawn the next day.

In the morning we followed their tracks. The sun had not come out, but the brightness of the sky had whitened the houses. Women peeped out of their doors and hurried off in search of the Marys. Gathered in the bright desolation of the great square, the black-robed Madonnas, like the Sisters, wandered aimlessly. At their feet, the flames of the candles, consumed in great clumps, flickered faintly in the breeze of the clear April morning, smelling of incense and wax. Close-up, the almost transparent faces of the Madonnas were awe-inspiring, so truthful were they with their shining eyes turned to heaven. On their hands, outstretched in search, lay in fine folds the white handkerchief of weeping, and in their breasts was thrust the silver dagger. Sometimes the air moved the thin laces of their robes and the Madonnas seemed to be alive.

The bearers, tired and sleepless, had sat on the ground at the feet of the statues, which now stood still in the middle of the square. As soon as the sun rose over the rooftops, the Madonnas were driven away through different streets and hurried to their churches, their long veils lifted by the wind.[78]

Compared to Cantatore's account, which refers to the 1910s, today the sepulchres in churches are set up in a more sober manner: however, the Archconfraternity of the Carmine stands out, which in the church of the same name takes advantage of the ritual of the sepulchres to set up and display the same statues that will be carried in procession the next day. The painter, moreover, recalls how along the winding and characteristic streets of Ruvo, as well as in neighboring towns, it was a well-established rite to carry the statues depicting Our Lady of Sorrows from each church on their shoulders to stop at the various sepulchres scattered throughout the town. However, in 1936 the bishop of Ruvo and Bitonto, Andrea Taccone, abolished the rite.[79]

Good Friday

[edit]The procession of the mysteries

[edit]

On Good Friday, the day of the commemoration of Jesus' death, the rites begin in the early afternoon hours, specifically at 12:00 p.m.[80] when the statue of the dead Christ is carried on the shoulders, announced only by incessant drumbeats, from the Carmine Church to the cathedral. Since a few years, in fact, the archconfraternity of Carmine has resumed the rite of the "Three Hours of Agony": the ceremony, which existed until the 19th century, consists of the meeting during the Eucharistic celebration between the simulacrum of Our Lady of Sorrows, already present in the cathedral, and the dead Christ to symbolize the meeting between the Virgin and her now lifeless son.[81] In ancient times during the mass there was a preacher who through gestures and words tried to impress the audience, creating suggestion and emotion among the faithful.[81] Meanwhile, at 5:30 p.m., the procession of the mysteries winds its way from the Church of Carmel. Opening the procession is, as per tradition, the penitential cross, followed by the banner of the mysteries bearing the symbols of Christ's passion. After the procession of the sisters and brethren, the first simulacrum to leave the church is that of Jesus in the Garden, always accompanied by Pancaldi's Eternal Sorrow march: the statue is surrounded by flowers and an olive branch, affixed to recall the Garden of Gethsemane; it is followed by the wooden statue of Christ at the Column, Ecce Homo, dressed in a red purple cloak, and Jesus at Calvary,[48] accompanied on its exit by Vincenzo Jurilli's funeral march Il Calvario.

The simulacrum of Jesus at Calvary is preceded by the “crestudd,” that is, children dressed as the Christ carried in the procession is depicted and also equipped with a small and light cross carried on their shoulders;[82] the statue of Calvary is followed by a long trail of believers who, out of devotion or to request or pay homage to some grace, also parade behind the statue barefoot.[46] The Jesus at Calvary is followed by the statue of Veronica, the crucified Jesus, Our Lady of Sorrows, and the small temple of the Holy Wood,[48] whose relic is placed by the spiritual father at the time of the exit of the canopy.[83] Shortly after the exit, the procession arrives in front of the cathedral, allowing the Dead Christ to enter. The procession branches off through the alleys of the town in a very slow manner cadenced by the notes of the funeral marches, until it arrives, just as it does for the Eight Saints, in front of the Purgatory Church where the Jesus at Calvary is turned toward the statue of the Pieta.[82] The procession resumes its very slow march, the total number of bearers being close to 300 or 400 men. The most evocative moment of the procession is marked by the passage through Corso Giovanni Jatta: the completely darkened avenue is illuminated only by the lamps that surround the statues; the various simulacra, representing the sufferings and pains endured by Christ, parade in chronological order. The mysteries go along the main streets at a very slow pace, in the evening they reach the hospital and around 8 p.m. they reach Corso Carafa, which is also in darkness. In the final stages of the procession in Largo Cattedrale, the spiritual father gives a blessing to the faithful with the relic of the holy wood, granting a moment of rest to the bearers. Around 11 p.m. the procession of mysteries turns to its withdrawal: with skill the statues are carried one at a time inside the church to the mournful notes of Petrella's Jone march.

Holy Saturday

[edit]Procession of the Pieta

[edit]

Holy Saturday shopping and the activities of stores that have been open since the early afternoon come to an abrupt halt as early as 4 p.m. when the band plays, at a steady pace, Angelo Lamanna's Pieta. At 4:30 p.m., in a completely packed Largo San Cleto, where the Church of Purgatory is located, the exit of the Pietà is witnessed with the band starting with the funeral march Rassegnazione, by Alessandro Amenduni, which is followed by the hymn to the Pietà, also known as "Le tue pupille roride," sung by the brethren and sisters.[84]

The simulacrum is immediately hoisted onto the shoulders of the bearers and made to swing on the parvis, captivating the audience in front of the scene of a suffering Mary with Christ resting on her knees.[58] Preceding the statue is the figure of the Cyrenian, dressed in black and hooded, whose identity is known only to the prior of the confraternity. The procession and the statue pass through part of the historic center in the early afternoon and then head to the hospital, an obligatory stop that is common to all other processions.

The statue of the Pieta along with the Jesus at Calvary is the most revered simulacrum of the entire Ruvestine Holy Week: until a few decades ago, the statue was covered with donations from the population, who resorted to the Virgin Mary to ask for a grace or to stop the increasingly frequent drought.[56] Moreover, the Pieta is the object of devotion especially by Ruvestine women and the sisters who, having long asked to remain closer to the statue during the procession, have resolved with the formula of a procession arranged in two wings, left and right, of mixed type, that is, one brother and one sister. The procession at nightfall passes through the darkened city streets, with the simulacrum illuminated by an arc of rose-shaped lamps above the two subjects.[57] The re-entry, followed by the faithful, takes place around 10 p.m. amid two wings of an orderly and participating crowd: in the glow of the light in Largo San Cleto, the statue is gradually carried inside the brightly lit Purgatorio Church. This is accompanied by the funeral march Holy Saturday with which the statue re-enters.

The procession of the Pieta closes the penitential rites of Ruvestine Holy Week.

Easter Sunday

[edit]The procession of the Risen Jesus and the bursting of the Quarantanas

[edit]

The Purification-Addolorata confraternity, after opening Ruvestine Holy Week with the procession of the Desolate, closes it with the procession of the Risen Jesus.[85] The mood is festive, completely different from previous days, and at 10:00 a.m. sharp the papier-mâché simulacrum crosses the threshold of St. Dominic's church for a brief tour of the city. As it passes by, instead of the white cloths symbolizing the shroud, multicolored cloths emerge from the windows; moreover, flower petals[85] are thrown from the terraces and windows at the simulacrum, preceded by a festive group of children waving the tricolor flag.[86]

The procession reaches along the city to the points where the various Quarantanas are hung:[85] as the statue arrives, balloons are inflated and launched, and the Quarantanas are burst after the explosion of a long series of pyrotechnic tricks.[87] Each burst is followed by a long applause of the jubilant crowd that along with merry marches celebrates the resurrection and Easter Sunday.[88] The simulacrum returns to the church of St. Dominic around 12:00 noon where, after mass, the last Quarantana is set off.

Easter Monday

[edit]Procession of the Annunziata

[edit]In Calendano, a hamlet 8 kilometers from Ruvo, the Easter rites come to a close with the procession of the Annunciation that winds its way from the Sanctuary of Santa Maria di Calendano. The simulacrum representing the archangel Gabriel announcing to Mary that she is pregnant with Jesus, whose liturgical solemnity falls on March 25, is also used to represent the angel announcing Christ's resurrection to the three Marys who have arrived at the tomb.[85] The procession is carried only through the streets of the small village and does not reach the town at all.[85]

Culinary traditions

[edit]With the arrival of Lent, as foods such as meat, cured meats, and fatty foods (including dairy products) disappear from the table, to make up for this lack the Ruvestine culinary tradition has always relied on vegetables and fish (above all cod and anchovies). The typical food of Lenten Fridays is undoubtedly the calzone, a rustic pizza stuffed with onions, salt cod, salted anchovies, black olives, and spaghetti. Typical of Maundy Thursday are salted anchovies to be served in the middle of a sandwich or to be topped with leeks and various vegetables. Another typical food is codfish used both in winter during the Christmas holidays, in this case fried, and in Lent, here, however, cooked over charcoal.[89] The typical Easter dessert is the scarcella,[90] strictly homemade[91] and made of short pastry and covered with “giuleppe” (which in Ruvestine dialect means icing), decorated either with chocolates and sugared almonds or hard-boiled eggs.[92] The Ruvestine scarcella can be of various shapes alluding to animals or everyday objects.[92]

Tourism and related events

[edit]Ruvestine Holy Week is among the twenty-one municipalities participating in the Holy Week in Apulia touristic and religious promotion project, sponsored by the Region of Apulia and managed by the Opera di Molfetta Cultural Association.[93] The project deals with the promotion of the rites of Holy Week through publications, conferences in the municipalities involved, collaborations with national and local media, and the creation of tourist itineraries hinged on the processional rites.[93] In addition, Ruvo hosts an annual national camper rally aimed at promoting the rites of Holy Week,[94] an event that has earned the Apulian town the title of Municipality Friend of Itinerant Tourism.[95] The flow of tourists also consists of the return to the hometown of numerous emigrants[73] and the stay of citizens from neighboring towns or southern Italy.[72]

The last two weeks of Lent are marked by the organization of several concerts of funeral marches organized by the confraternities or parishes, such as the Passion Music Concert established in 1982 by the Purification-Addolorata confraternity.[96] The promotion of Ruvo di Puglia's band repertoire and funeral marches has been carried out since 1993 by the Pino Minafra and the Band of Ruvo di Puglia ensemble, established at the behest of jazz musician Pino Minafra, also founder of the RuvoMusica association[97] and directed by maestro Michele Di Puppo. Minafra's project aims to re-evaluate the band tradition, to be considered not as a folkloric element but as a musical language, through the publication of albums dedicated to the music of Holy Week and international tours.[97] In fact, the RuvoMusica association published two collections of funeral marches from the Ruvo band tradition in 1994 and 2011. The rites of Holy Week in Ruvo di Puglia have also been the subject of publications and essays but also of several documentaries such as the 1979 RAI documentary and the Südwestrundfunk documentary filmed in 2015 and aired on April 9, 2017.[98]

In conjunction with Holy Week, the Pro Loco of Ruvo is responsible for setting up a photographic exhibition, Time Memory Tradition, which collects more than fifty years of photographic shots related to processional rites and provides informational brochures about the events.[99] For several years the Municipality of Ruvo has sponsored the photo contest A Click on Your Holy Week, established in 2010.[100] In addition to the occasional television reports made during Ruvo's processions, the rites are streamed live on ruvesi.it online TV.[101]

On March 27, 2013, an event was held at Avitaja Palace in which the Italian Post Office issued a philatelic cancellation dedicated to the procession of the Eight Saints.[102]

Since 2022, Ruvo's Pro Loco has been organizing guided tours of the historic center and key places of Ruvo's Holy Week on the night of the departure of the procession of the Eight Saints.

Discography

[edit]- Passione e Morte - Le Musiche Della Settimana Santa A Ruvo Di Puglia, Ruvomusica, 1994

- I Giorni del Sacro - suoni e gesti della Settimana Santa in Puglia, Genius Loci, 2000

- La Banda - Musica sacra della Settimana Santa, Enja Records, 2011

Filmography

[edit]- Passione e Morte - I riti, i suoni, le immagini della Settimana Santa a Ruvo di Puglia, 1994 (VHS)

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ AA.VV. (1999, p. 6).

- ^ "Patrimonio immateriale d'Italia". 2011. Archived from the original on 9 July 2013. Retrieved 10 March 2013.

- ^ "Tradizioni culturali di Ruvo di Puglia". 2012.

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 29).

- ^ a b Di Palo (1994, p. 31).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, pp. 31–34).

- ^ a b c "La storia della Confraternita di San Rocco". 2011.

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 30).

- ^ Anonimo (1633), p. 6.

- ^ a b AA.VV. (1999, p. 13).

- ^ a b c AA.VV. (1999, p. 17).

- ^ a b c Di Palo (1994, p. 113).

- ^ a b c "La storia dell'arciconfraternita del Carmine". 2011. Archived from the original on 5 March 2016. Retrieved 31 March 2012.

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 33).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 36).

- ^ a b Francesco Stanzione. "La Settimana Santa a Ruvo di Puglia (BA)".

- ^ "Biografia di Papa Cleto". 2000.

- ^ a b Di Palo (1994, p. 25).

- ^ a b c "La storia della Confraternita del Purgatorio". 2011. Archived from the original on 29 October 2013. Retrieved 1 April 2012.

- ^ a b "I Domenicani a Ruvo: dall'ospizio al convento".

- ^ a b "Le confraternite a Ruvo nel 1700". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- ^ "Raccolta di documenti".

- ^ a b "Le confraternite a Ruvo nel 1800". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- ^ a b Di Palo (1999, p. 21).

- ^ a b Francesco Stanzione. "Le marce funebri Ruvo di Puglia (BA)".

- ^ Di Palo (1994, pp. 63–65).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 66).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 69).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 68).

- ^ a b Di Palo (1994, p. 71).

- ^ a b c d "Centenario della statua di Maria S.S. Desolata". 11 February 2011.

- ^ Redazione (2020-04-03). "LA STORIA DEL CORTEO PROCESSIONALE DELLA DESOLATA: PROBABILMENTE NON SI TENNE DAL 1941 AL 1947". Ruvesi.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- ^ "Le Confraternite a Ruvo - 1900". 18 February 2011. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- ^ Massimiliano De Silvio (2012). "Settimana Santa 2012". Archived from the original on 4 April 2015.

- ^ AA.VV. (1999, p. 24).

- ^ AA.VV. (1999, p. 27).

- ^ AA.VV. (2002, pp. 14–16).

- ^ Salvatore Bernocco (2007). "La storia della Parrocchia SS. Redentore".

- ^ a b c AA.VV. (1999, p. 28).

- ^ AA.VV. (1999, p. 5).

- ^ AA.VV. (1999, p. 35).

- ^ "Gli Otto Santi in una vetrata per la Chiesa di S. Rocco. Il 27/10 la benedizione". 21 October 2011.

- ^ "Terminati i lavori al complesso statuario degli "Otto Santi"o "Deposizione". Stasera presentazione". 6 March 2014. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015.

- ^ a b Di Palo (1994, p. 53).

- ^ a b c Di Palo (1994, p. 140).

- ^ a b Di Palo (1994, p. 138).

- ^ "Il restauro del Gesù al Calvario. Resoconto della presentazione del 12 dicembre". Il Sedente. 13 December 2011.

- ^ a b c Di Palo (1999, p. 16).

- ^ A small temple particularly similar to the one that was destroyed in the 1950s is located in Bitonto and is carried in procession on Good Friday.

- ^ Redazione (2020-04-10). "IL CORTEO PROCESSIONALE DEI SS MISTERI DALL'800 A OGGI". Ruvesi.it (in Italian). Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 40).

- ^ Michele Montaruli (11 February 2011). "Processione dei misteri - Singolare Curiosità". Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- ^ "LA STATUA DELLA VERONICA FARA' PARTE DELLA PROCESSIONE DEI "SS. MISTERI"". 14 January 2018.

- ^ Paolo M. Pinto (12 July 2022). "RESTAURO DI GESU' NELL'ORTO, CONVERSAZIONE CON FRANCESCO DI PALO".

- ^ a b c d e f "La Madonna della Pietà". 2013.

- ^ a b c Di Palo (1994, p. 144).

- ^ a b Di Palo (1999, p. 9).

- ^ a b Di Palo (1994, p. 148).

- ^ "Il programma del Carnevale a Ruvo". 2012. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 3 April 2012.

- ^ Francesco Stanzione. "La Quarantana".

- ^ Francesco Stanzione. "L'adorazione della Croce".

- ^ a b c Di Palo (1994, p. 87).

- ^ Di Palo (1999, p. 2).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 88).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, pp. 89–93).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 89).

- ^ a b Di Palo (1994, p. 93).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 97).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 99).

- ^ "Sacra rappresentazione". 2011. Archived from the original on 23 September 2015.

- ^ Teresa Fiore (2012). "Sacra rappresentazione del mercoledì Santo 2012". Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- ^ a b c Di Palo (1994, p. 107).

- ^ a b c d Di Palo (1994, p. 110).

- ^ a b c Di Palo (1994, p. 115).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, pp. 117–118).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 120).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 121).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, pp. 81–83).

- ^ "Una tradizione scomparsa: le "Marie" ai Sepolcri del Giovedì santo". Il Sedente. 13 April 2011.

- ^ Until 2016, the transport of the dead Christ to the cathedral took place around 3 p.m. At the end of the service, the simulacrum would return, around 6 p.m., to the Church of the Carmine, where it would join the procession, immediately after the exit of the crucified Christ and immediately before Our Lady of Sorrows, simulating the meeting between the mother and her lifeless son.

- ^ a b Di Palo (1994, p. 127).

- ^ a b Di Palo (1994, p. 131).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 130).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 143).

- ^ a b c d e Di Palo (1994, p. 160).

- ^ Di Palo (1999, p. 10).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 157).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 162).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, pp. 57–60).

- ^ Di Palo (1994, p. 78).

- ^ Di Palo (1999, p. 31).

- ^ a b Di Palo (1994, p. 76).

- ^ a b "Settimana Santa in Puglia - Progetto di promozione turistico-religiosa" (PDF). Associazione Culturale Opera. 2009.

- ^ Vito Cappelluti (10 April 2012). "Concluso con successo il raduno camper "La Settimana Santa a Ruvo di Puglia"". Archived from the original on 15 July 2014.

- ^ Vito Cappelluti (2012). "Il Camper Club di Ruvo di Puglia è in festa!". Archived from the original on 31 August 2013.

- ^ "Concerto tradizionale della Settimana Santa alla Chiesa di San Domenico". ruvolive.it. 20 March 2013.

- ^ a b "Pino Minafra e la Banda". minafrasprod.com. 2011. Archived from the original on 23 August 2013. Retrieved 2 April 2013.

- ^ "Osterbräuche, 9.4.2017". Südwestrundfunk. 2017. Archived from the original on 11 April 2017. Retrieved 11 April 2017.

- ^ "Inaugurata mostra fotografica: "Tempo Memoria Tradizione... Settimana Santa a Ruvo di Puglia"". ruvolive.it. 23 March 2013.

- ^ "Quarta edizione del concorso "Un click sulla tua Settimana Santa"". unclicksullatuasettimanasanta.it. 1 March 2013. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014.

- ^ "Settimana santa live in streaming". ruvesi.it. 2015. Archived from the original on 1 April 2015. Retrieved 2 April 2015.

- ^ ""Annullo filatelico per la processione degli Otto Santi". 27 March 2013.

Bibliography

[edit]- Anonimo Autore di Veduta (1633). Historia del combattimento de' tredici italiani con altrettanti francesi. Napoli.

- Francesco Di Palo (1994). Passione e Morte. Fasano: Schena.

- Francesco Di Palo (1999). I Giorni del Sacro. Terlizzi: Centro Stampa Litografica.

- AA.VV. (2002). Otto Santi - storia e restauro. Terlizzi: Centro Stampa Litografica.